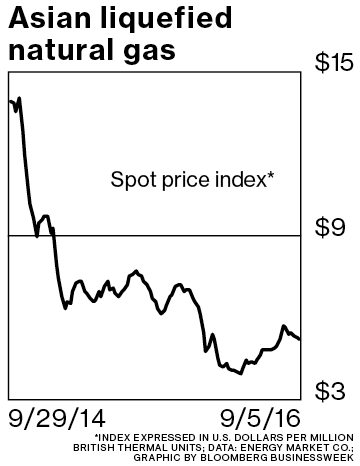

But since the vessel was ordered three years ago from Daewoo Shipbuilding & Marine Engineering, supplies of onshore gas have risen, and the number of smaller competing ships has grown—lowering ship-leasing rates and dimming the appeal of the floating megafactory. That means the gas complex may sit idle after delivery.

For now, Mitsui O.S.K. is scouting for short-term business to get some cash in the door. Although the vessel could also function as a regular LNG carrier, there’s little demand for one-off delivery jobs for units of its size, says David Boggs, managing director of Singapore-based consulting firm Energy Maritime Associates. “They could lay it up and leave it in the shipyard, or tell the shipyard to take their time” finishing construction, Boggs says. “That’s still cheaper than taking delivery and just having it sit with no business.”

Mitsui O.S.K. won’t disclose the cost of idling the vessel, says Yuki Fujiwara, a spokesman for the Tokyo-based shipping line. “We can still make a profit with the ship over its 20-year contract even if we can’t find a home for it for the first year and a half,” he says. Still, Hashimoto is confident growing demand for LNG will increase the chances of finding work. “We’re looking for a temporary job where we can deploy the ship,” he says. “There are places in Asia and South America with such a need.”

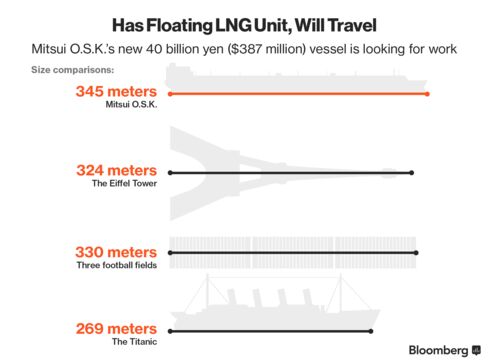

Even if the big boat finds a temporary job, it may struggle to work to its full capacity. Today, some smaller LNG vessels in Asia aren’t fully deployed. And with the capacity to store 263,000 cubic meters (862,861 cubic feet) of LNG, Mitsui O.S.K.’s 345-meter vessel will be bigger than any other so-called floating storage regasification unit, or FSRU, on the water.

The ship’s size will make it harder to efficiently deploy, says Richard Nelson, a Singapore-based partner specializing in energy at law firm King & Spalding, who estimates that smaller FSRUs in Southeast Asia are already using no more than 30 percent of their capacity. “There’s a question generally about how to deploy FSRUs at anywhere near 100 percent capacity,” he says, “and the bigger the vessel, the more of an issue that becomes.”

Egypt and Pakistan started importing LNG for the first time last year using the units, despite predictions that Egypt wouldn’t have the infrastructure in place to get the fuel this decade, says Andrew Buckland, principal analyst for LNG shipping and trade at Wood Mackenzie, an energy research and consulting firm. He expects there will be at least 30 FSRUs globally by 2018, up from 23 at the start of 2016.

LNG imports from FSRUs could rise 26 percent this year, to 29 million metric tons, after jumping 44 percent in 2015, according to Wood Mackenzie. “It’s definitely the brightest spot of the LNG industry,” Buckland says. “FSRUs allow you to access gas far more quickly than building a land-based facility.”

SOURCE BLOOMBERG

No comments:

Post a Comment